Why debugging feels harder than it used to

In a single-process application running on your laptop, debugging often means one of three things: read an error message, set a breakpoint, or add a few print statements. In modern systems—microservices, serverless functions, container orchestration, managed databases, third-party APIs—those approaches frequently fail you for a few reasons:

- You can’t reproduce production easily. Data, load, timing, and distributed interactions matter.

- Failures are emergent. The bug isn’t in one place; it’s in the interaction between many components.

- The system is dynamic. Instances come and go, deployments are continuous, and configuration changes constantly.

- The signal-to-noise ratio is low. Logs are huge, metrics are abundant, and alerts often misfire.

The way out is a blend of classic debugging skills and modern observability: designing systems so you can answer questions about what they’re doing, even under novel failure modes.

This article focuses on practical techniques that work for junior developers (clear steps, checklists, examples) and also provide depth senior engineers expect (instrumentation strategy, tool tradeoffs, incident rigor).

Debugging vs. observability (and why you need both)

Debugging is the act of finding and fixing the root cause of incorrect behavior.

Observability is a property of a system: how well you can infer internal states from external signals.

A typical production investigation flows like:

- Detect: An alert triggers or a user reports a problem.

- Triage: Scope impact and identify the failing component or dependency.

- Diagnose: Narrow down causes using logs/metrics/traces/profiles.

- Mitigate: Roll back, feature-flag off, scale, or apply a hotfix.

- Resolve: Implement the real fix and prevent regressions.

- Learn: Postmortem + action items (code, alerts, runbooks).

Debugging is step 3–5; observability makes steps 2–4 tractable.

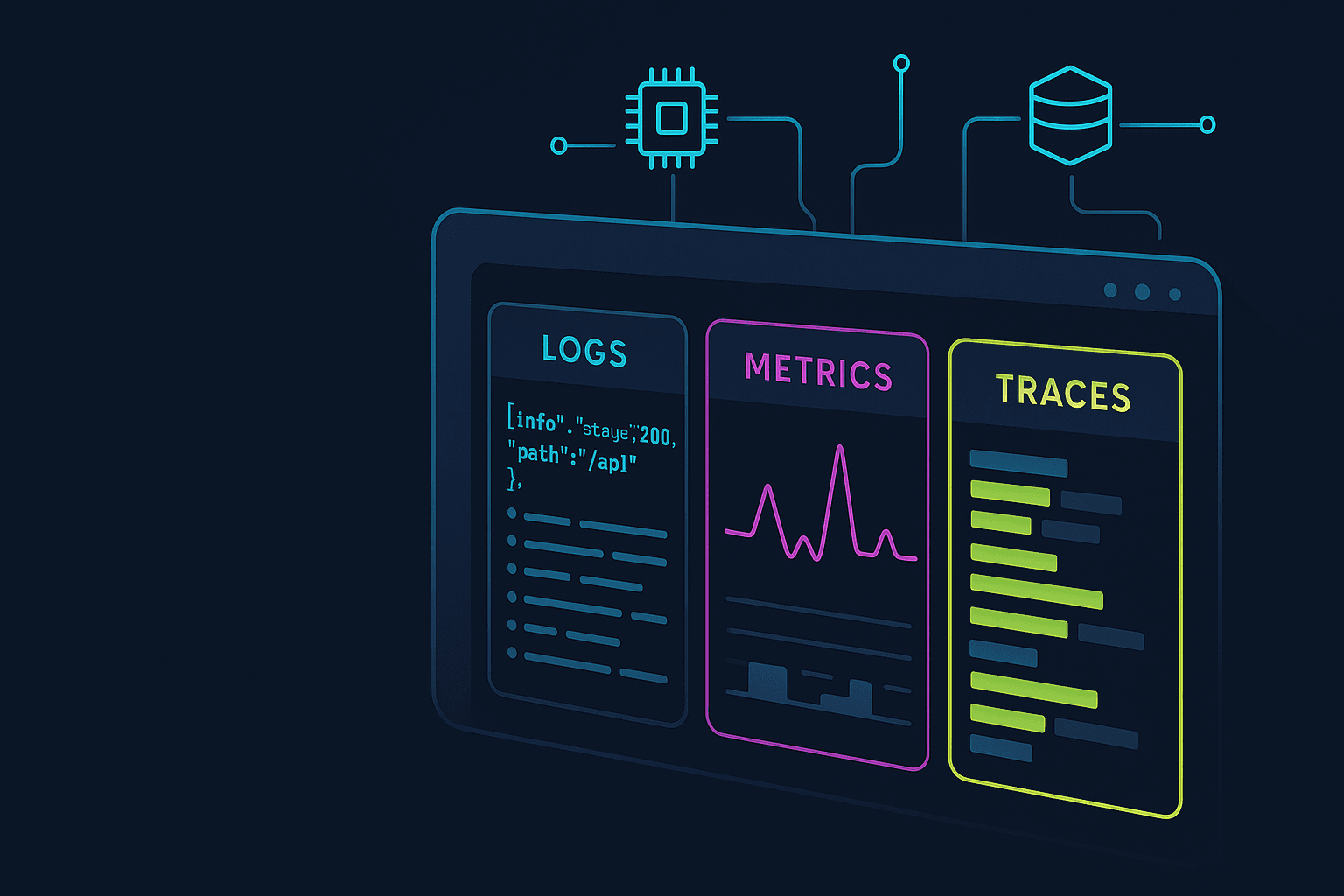

The three pillars: logs, metrics, traces

You’ll hear this phrase a lot, but it’s worth being concrete.

Logs

Logs are discrete events. Great for:

- error details and stack traces

- user/session context

- branching decisions (e.g., feature flag path)

- interactions with external services

Best practice: structured logs, not unstructured strings.

Metrics

Metrics are numeric time series. Great for:

- SLOs and alerting (latency, availability)

- throughput and saturation (RPS, queue depth)

- capacity planning

Best practice: use histograms for latency, not averages.

Traces

Traces capture end-to-end request flow across services. Great for:

- identifying where time is spent

- attributing errors to a specific hop

- understanding fan-out and concurrency

Best practice: consistent trace context propagation and sensible sampling.

These pillars reinforce each other: metrics tell you something is wrong, traces show where, logs explain why.

A practical incident workflow (what to do when paged)

When something breaks, you want a repeatable method.

1) Start with impact and scope

Answer:

- Who is affected? (all users vs. a cohort)

- What is affected? (endpoint, region, tenant)

- When did it start? (after deploy? config change?)

Tactics:

- Check your status page / incident channel.

- Correlate with deploy timeline (Git SHA, release tag).

- Compare regions/tenants: if only one region is broken, think infra or configuration.

2) Look at golden signals

Use the four “golden signals” (popularized by SRE):

- Latency: p50/p95/p99

- Traffic: requests/second

- Errors: error rate, failed requests

- Saturation: CPU, memory, queues, thread pools

A useful pattern: latency up + error up often means a dependency is timing out; latency up + errors flat may indicate resource contention.

3) Use traces to localize the bottleneck

Look at slow traces and ask:

- which span dominates latency?

- is there a retry storm?

- are errors coming from a downstream service?

4) Use logs to confirm hypotheses

Once you suspect a component, query logs by:

trace_idrequest_iduser_idor tenant- error code

5) Mitigate first, then fix

If you can reduce user harm quickly:

- roll back

- disable a feature with a flag

- increase timeouts temporarily (careful—can worsen load)

- add capacity

Then proceed to root cause.

Structured logging: the single highest ROI upgrade

If your logs are strings like:

User 123 failed to checkout

…you’ll struggle to query and correlate at scale.

Instead, emit structured JSON logs:

json{ "level": "error", "msg": "checkout_failed", "user_id": "123", "order_id": "o_456", "error": "Card declined", "trace_id": "4bf92f3577b34da6a3ce929d0e0e4736", "span_id": "00f067aa0ba902b7" }

Node.js example (pino)

jsimport pino from 'pino' const logger = pino({ level: process.env.LOG_LEVEL ?? 'info', base: null, // don’t auto-add pid/hostname if you don’t want }) export function checkout(req, res) { const log = logger.child({ trace_id: req.headers['traceparent'], user_id: req.user?.id, }) try { // ... log.info({ order_id: 'o_456' }, 'checkout_started') // ... } catch (err) { log.error({ err }, 'checkout_failed') res.status(500).json({ error: 'internal_error' }) } }

Key ideas:

- Log events, not paragraphs: use stable message keys (

checkout_failed) and attach fields. - Include correlation IDs (trace IDs, request IDs).

- Avoid sensitive data (tokens, passwords, raw PII). Use redaction.

Debugging tip: log “decision points”

When debugging complex logic (feature flags, routing, caching), log the branch taken:

json{ "msg":"cache_decision", "hit":false, "reason":"stale_ttl", "key":"user:123" }

It’s far more actionable than “cache miss”.

Correlation IDs: request_id and trace_id

In distributed systems, a single user action can touch many services. Without a shared ID, you’re guessing.

Minimal: request ID propagation

- At the edge (API gateway / ingress), generate

X-Request-Idif missing. - Forward it to every downstream HTTP call.

- Include it in every log line.

Better: W3C Trace Context

Use traceparent and tracestate headers. Most tracing systems and OpenTelemetry support it.

Even if you aren’t ready for full tracing, adopting the headers now makes future tracing easier.

Distributed tracing with OpenTelemetry

OpenTelemetry (OTel) is the de facto standard for instrumenting traces, metrics, and logs.

What tracing gives you

- A trace represents one request.

- A trace consists of spans (e.g., inbound HTTP, DB query, downstream call).

- Each span has timing, attributes (tags), and status.

Python example: instrument FastAPI

pythonfrom fastapi import FastAPI from opentelemetry import trace from opentelemetry.instrumentation.fastapi import FastAPIInstrumentor from opentelemetry.instrumentation.httpx import HTTPXClientInstrumentor app = FastAPI() FastAPIInstrumentor.instrument_app(app) HTTPXClientInstrumentor().instrument() tracer = trace.get_tracer(__name__) @app.get("/pay") async def pay(user_id: str): with tracer.start_as_current_span("validate_user") as span: span.set_attribute("app.user_id", user_id) # ... validation logic ... return {"ok": True}

Add attributes carefully:

- Good:

tenant_id,endpoint,db.system,http.status_code - Risky: raw emails, names, tokens

Sampling: don’t drown yourself

Tracing every request can be too expensive. Options:

- Head-based sampling: decide at request start (simple, can miss rare errors).

- Tail-based sampling: decide after seeing the whole trace (better for “keep errors and slow traces”, more complex).

A strong baseline:

- keep 100% of error traces

- keep a percentage of normal traces (e.g., 1–10%)

- keep all traces above a latency threshold (tail-based)

Metrics that actually help: RED, USE, and histograms

RED method (request-driven services)

- Rate: requests per second

- Errors: error rate

- Duration: latency distribution

USE method (resource-driven)

- Utilization

- Saturation

- Errors

Latency: avoid averages

An average hides pain. Use histograms and percentiles.

Prometheus-style histogram example (conceptual):

http_request_duration_seconds_bucket{le="0.1"}...{le="0.25"}...{le="0.5"}

Then compute p95/p99 in your dashboard.

Debugging tip: compare p50 vs p99

- p50 steady, p99 spikes: usually tail latency from GC, lock contention, cold caches, or a flaky dependency.

- p50 and p99 rise together: systemic overload or a broad regression.

Profiling in production: CPU, memory, and contention

When latency rises but logs and traces don’t show an obvious external dependency, profiling is often the fastest path.

Types of profiling

- CPU profiling: where time is spent (hot functions)

- Memory profiling: leaks, high allocation rates

- Lock contention profiling: blocking and waits

Tools

- eBPF-based profilers (Parca, Pixie, Datadog Continuous Profiler): low overhead, production-friendly.

- Language-specific:

- Java: JFR (Java Flight Recorder)

- Go:

pprof - Python:

py-spy(sampling),cProfile(higher overhead)

Go example: pprof endpoints

goimport _ "net/http/pprof" import "net/http" func main() { go func() { http.ListenAndServe("127.0.0.1:6060", nil) }() // ... run server }

Then:

bashgo tool pprof http://127.0.0.1:6060/debug/pprof/profile?seconds=30

Debugging technique:

- Take a profile during the incident.

- Take another after mitigation.

- Compare flame graphs to isolate what changed.

Debugging common production failure modes

1) Timeouts and retries (the silent outage amplifier)

Symptoms:

- rising latency

- rising error rate (often 5xx)

- higher downstream traffic than normal

Anti-pattern: unbounded retries with no jitter.

Best practice:

- set strict timeouts per dependency

- use exponential backoff + jitter

- cap retries

- use circuit breakers

Pseudo-code pattern:

pseudofor attempt in 1..max_retries: try call(dep, timeout=200ms) catch timeout: sleep(jittered_backoff(attempt)) throw error

Debugging tip:

- Use tracing to see repeated spans.

- Add a metric like

retries_total{dependency="payments"}.

2) Connection pool exhaustion

Symptoms:

- requests hang

- DB shows max connections reached

- app threads stuck waiting

Fixes:

- size pools correctly

- close connections (ensure

finallyblocks) - reduce per-request concurrency

Debugging tip:

- export pool metrics: in-use, idle, wait time

- thread dump (Java) or goroutine dump (Go)

3) Memory leaks and GC pressure

Symptoms:

- memory climbs steadily

- GC time increases, tail latency spikes

- eventual OOMKills

Fixes:

- find retained objects (heap dump)

- reduce allocations (hot paths)

- fix caches with eviction limits

Debugging tip:

- correlate p99 latency spikes with GC metrics

- use continuous profiling to identify alloc hotspots

4) Thundering herd / cache stampede

Symptoms:

- after cache expiry, DB load spikes

- latency spikes periodically

Fixes:

- request coalescing / singleflight

- probabilistic early refresh

- staggered TTLs

Tooling comparisons (practical tradeoffs)

Logs

- Elastic / OpenSearch: powerful search, heavy to operate at scale.

- Loki: cheaper for high-volume logs, great with Grafana; favors labels over full-text indexing.

- Cloud-native (CloudWatch, Stackdriver, Azure Monitor): easy to start, can get expensive; querying varies in ergonomics.

Guideline: if cost is a concern and you have Grafana, Loki is often attractive; if you need complex full-text search and analytics, Elastic-style systems shine.

Metrics

- Prometheus: standard, pull-based, great ecosystem.

- Grafana Mimir / Cortex: horizontally scalable Prometheus-compatible backends.

- Cloud managed: easier operations, sometimes limited flexibility.

Guideline: start with Prometheus semantics even if you use managed backends—portability matters.

Tracing

- Jaeger: classic, popular in Kubernetes.

- Zipkin: simpler, older ecosystem.

- Grafana Tempo: cost-effective, integrates with Grafana and exemplars.

- Vendor APMs: polished UX, advanced features (tail sampling, service maps), higher cost.

Guideline: choose based on operational load + team maturity. If you don’t have staff to run storage clusters, managed APM might be cheaper in time.

Designing for debuggability (code-level best practices)

1) Make errors actionable

A production error should help answer:

- what failed?

- where?

- for which user/tenant/request?

- due to which dependency?

In many languages, wrap errors with context.

Example (Go):

goreturn fmt.Errorf("fetch user %s from db: %w", userID, err)

2) Use typed error categories

Instead of string matching, define categories:

- validation_error (4xx)

- dependency_timeout (5xx)

- dependency_unavailable (5xx)

- internal_error (5xx)

This enables:

- better alert routing

- accurate SLO accounting

- faster triage

3) Don’t swallow stack traces

When rethrowing, preserve the original stack (language/framework dependent). In JavaScript/TypeScript, rethrowing a new error can lose context unless you attach cause:

jsthrow new Error('payment failed', { cause: err })

4) Instrument boundaries, not every line

Tracing and metrics should focus on:

- inbound requests

- outbound calls

- DB queries

- queues

- critical business steps

Too much instrumentation becomes noise and cost.

Debugging techniques that scale

Binary search your changes

If you have a regression and many commits, use git bisect:

bashgit bisect start git bisect bad HEAD git bisect good v1.2.3 # test each suggested commit until culprit found

Even senior engineers underuse this. It’s one of the fastest “root cause” tools when reproduction exists.

Add temporary diagnostics safely

Sometimes you need extra visibility. Do it without redeploying repeatedly:

- Feature-flagged debug logging for a single tenant/request ID.

- Dynamic log level toggles (with guardrails).

- Runtime config for sampling rates.

Example strategy:

- a config entry:

debug_user_id=123 - only log verbose fields when

req.user_id == debug_user_id

Reproduce production behavior locally

Make reproduction more realistic:

- Use production-like datasets (sanitized)

- Use the same versions of dependencies

- Simulate latency and failures (toxiproxy, tc netem)

Network fault injection examples:

- add 200ms latency to a DB connection

- inject 1% packet loss

- force a dependency to return 500s

This helps confirm whether your retry logic, timeouts, and circuit breakers behave.

Alerting and SLOs: fewer pages, better signal

Alerting that fires constantly trains teams to ignore it. Make alerts reflect user impact.

Use SLO-based alerts

An SLO says: “X% of requests succeed within Y ms over Z time.”

Alert when you burn error budget too fast.

Benefits:

- fewer false positives

- alerts correlate with customer pain

Separate symptom alerts from cause alerts

- Symptom: user-facing latency/error SLO burn (page-worthy)

- Cause: CPU high, queue depth high (ticket-worthy, supports diagnosis)

Security and privacy in observability

Observability data often contains sensitive context.

Best practices:

- Redact secrets at source (before logs leave the process).

- Hash or tokenize identifiers when possible.

- Access controls: production logs/traces are sensitive.

- Retention policies: keep what you need, delete what you don’t.

Be especially careful with:

- Authorization headers

- Session cookies

- Password reset links

- Raw payloads containing PII

A concrete “put it together” example: tracing + logs + metrics

Imagine an endpoint /checkout timing out.

Step 1: Metrics show a problem

Dashboard:

checkout_request_durationp99 jumps from 800ms to 8s- error rate rises from 0.2% to 7%

Step 2: Traces localize it

Slow traces show:

POST /checkouttotal: 8.2spayments.chargespan: 7.9s (dominant)- multiple retries visible

Hypothesis: payment provider latency increased or your client is retrying too aggressively.

Step 3: Logs confirm cause

Query logs by trace_id from a slow trace. You find:

payment_timeoutevents- retries without jitter

- a recent config change set timeout to 5s and retries to 3 (worst-case 15s)

Step 4: Mitigate

- reduce retries to 1

- add jitter

- set an overall request deadline

Step 5: Prevent recurrence

- add metrics for retry count and timeout rates

- add an alert on dependency latency

- update runbook: “if payment latency spikes, cap retries and enable circuit breaker”

This is the core loop: metrics detect, traces localize, logs explain.

Best practices checklist

Instrumentation

- Structured logs with stable event keys

- Trace context propagation across all services

- Latency histograms (p95/p99) for key endpoints

- Dependency metrics (timeouts, retries, error rates)

Operational readiness

- Dashboards for golden signals

- SLO-based paging alerts

- Runbooks linked from alerts

- Deployment markers on graphs

Code hygiene

- Actionable errors with context

- Timeouts everywhere (client and server)

- Bounded retries with jitter

- Feature flags for risky changes

Safety

- Redaction of secrets and PII

- Access controls for observability data

- Reasonable retention policies

Closing thoughts

Modern debugging is less about staring at a single stack trace and more about navigating a system with many moving parts. The most effective teams don’t “debug harder”; they engineer systems to be debuggable.

If you’re improving an existing codebase, start small:

- introduce structured logging and correlation IDs

- add basic RED metrics and p95/p99 latency

- instrument distributed tracing with OpenTelemetry

- adopt a lightweight incident workflow and SLO-based alerting

Each step compounds the value of the next. Over time, production issues shift from chaotic firefights to disciplined investigations—faster, calmer, and far less disruptive.